I recently read an article that proclaimed the end of mobile apps, insisting that RWD (Responsive Web Design) and Progressive Web Apps (PWA) were the answer to all companies’ needs. The author was using app downloads figures to support this allegation. As Frederick Brooks said, there is no miraculous technique (no “silver bullet”) in software engineering. Using figures is not so simple and there are many traps that can lead us to false conclusions.

Let’s take a look at the different logical biases related to this topic.

Web or native?

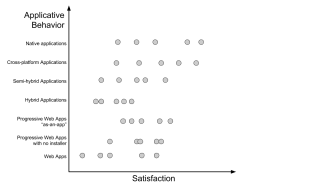

Let’s imagine that we want to evaluate the user satisfaction for various applications: pure native applications, cross-platform applications, semi-hybrid applications with React Native, “installed” PWAs on Android 6, not-installed PWAs and non-progressive Web App. With these measurements, we would be able to produce a graph with the level of satisfaction on the x-axis while the y-axis represents how close to a “native application” the app is.

Our first graph shows the user satisfaction for each group of application depending on the app technical similarities with native applications.

It is hard to make any precise conclusion, however we can identify a global trend by analyzing the average satisfaction of each group of applications: the most “native” apps seem to be more likely to generate satisfaction.

Depending on the type of application?

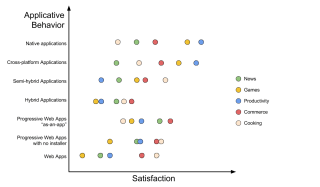

Now let’s imagine that satisfaction depends on the type of application. In other words, the satisfaction now depends on the category in which you would place each application on an application marketplace.

So it’s not so easy, right?

Trends appear to be less obvious.

We quickly realize that the displayed categories are very limited. There is no social networks, for example. So here we have an extremely fragmented view of the market, which can significantly change the relevance of the previous conclusions. This bias is very common in studies that I read here and there. Be careful.

For the sake of the argument, let’s assume that this is not a problem for us (in this scenario, we are interested in these exact types of applications) and let’s continue the analysis.

Depending on the category, the relationship between customer’s satisfaction and the application type is not the same: the best productivity tools and the best games, for example, seem to be appreciated when they feel close to the native feeling. On the other hand, cooking applications which are “native” do not seem to be appreciated by customers. This observation makes sense if we look closely at the application technical requirements: productivity tools often need to read of write files, therefore need a performant way to call the operating system features. In the same way, games need power and a good control of parallel programming, that’s why they are developed to the closest of the operating system.

Having said all of that, we could think that we should be able to find trends by applying common sense logics to all categories. A game would always be better as a native application whereas a cooking website would be better as a WebApp… But quickly, we realize that this logic does not work for all categories. E-Commerce, for example, does not seem to be affected by the type of applications…

What about budgets?

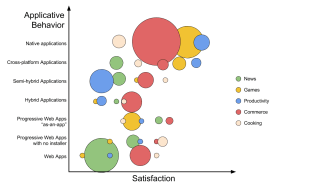

What if the applications do not receive the same funding according to their type or their development platform? We’re going to analyze this possibility and compare the budget allocated to each type of application.

Still not obvious, huh

Native applications seem to cost more, which is understandable: they need to be developed on two or three different systems whereas cross-platform or web development can easily be used on different hardwares. But this statement is not an absolute. On this graph, we can see that a high cost for a semi-hybrid office application. It’s impossible to know if this cost is a chosen investment or if it’s the consequence of a bad choice of technology coupled with stubbornness.

We can also notice another visible trend: we found high costs for eCommerce applications. But we don’t know if it’s because eCommerce applications are more expensive to develop or if it’s because the return on investment is judged more promising.

But then, numbers don’t mean anything?

Numbers are very difficult to interpret because causes and effects get muddled up when you mix an underlying technology and a functional need. We have a real paradox here, called the “Yule-Simpson paradox”: regardless of the constituent groups (price, objective, satisfaction…), the different correlations observed are not consistent with what is observed in each of the groups. There is a lack of information that influences all factors.

There is a good example which could illustrate this problem, an example that I would call “the impossible application”. Imagine an application that will require all your skills, your teams’ time and an open access to the native features to create the perfect UX.

So you mobilize your teams, the development is long and expensive and… you fail. Nobody likes it, it’s not successfull. You have a perfect example of an application that is expensive to develop, a development which you would never have tried with an hybrid technology but which skews statistics and make you believe that the “native” was not the right solution. Here is the reality: we do not expect the same thing from a native app and an hybrid one.

We can imagine another good example: a client who needs to highly control his application interface. But he doesn’t judge relevant to invest in a cross-platform development because he says that ⅔ of mobile users never install applications other than social networks. However, its application was intended for a B2B target which was required to install the application for administrative purposes. This specific target and acquisition strategy completely invalidated the previous statistics.

An overall vision

In order to make good decisions, we must approach each project as a whole: functional and technical specifications, target analysis (age, socio-economic classification, location, culture …), information and skills level of the teams, existing development platform or acquisition capabilities, sustainability of the development, expected turnover, deployment and maintenance strategy…

For now, there is no Big Data algorithm able to take a step back from a need that, most of the time, the sponsor himself does not know how to formalize. It’s still necessary to spend time refining the need, analysing it, and to determine, every time, the different solutions (which can not be only technical).

If you want to say that the PWAs are promising and it’s time to get interested into them, go ahead (I surely believe in them myself). But I won’t say that we must, each time, give up the native applications and market places.

Whether you have doubts or not, get advice from people who have experience, who are knowledgeable and independent of the technologies employed.