Artists are not the only ones who suffer from a blank page, so are your users. Their frustration can lead them to abandon your page prematurely. Several techniques can help you to speed up rendering and avoid that problem. One of them is to defer parsing of JavaScript files.

Modern browsers are designed to render pages more quickly. For example, they scan the page as it comes in, looking for the URLs of resources which will be needed later in the rendering of the page (images, CSS but more specifically, JavaScript files). This is called a preload scan in Chrome and Safari, a speculative parsing in Firefox and a lookahead download in Internet Explorer. This feature allows the browser to start fetching the ressources while constructing its own modelisation of the HTML code, the Document Object Model (DOM) and its own modelisation of the CSS code, the CSS Object Model (CSSOM).

This is not a continuous process though, because of Javascript. As these scripts may modify HTML elements and their style, the browser stops building the DOM each time it fetch and parse a Javascript file. Afterwards the browser waits for a break into the CSSOM construction to execute the script. Since the DOM and the CSSOM are the backbone of rendering: no DOM & CSSOM, no rendering.

In this article, we will focus on what can be done about JavaScript files to improve render timings.

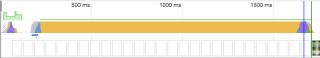

Even if the construction of the DOM (in blue) occurs mostly before the execution of JavaScript (in yellow), it only ends after. In this "default" configuration of script loading, the DOM is built very late. The display is delayed.

Distinguish critical and noncritical JS

To reduce the time to render, you must postpone the parsing of JavaScript files as often as possible. But if you try, you’ll see that it is not as simple as it seems.

Your JavaScript files are likely to contain several types of code portions and you may need to load some of them as soon as possible: JavaScript business-specific code (analytics, for example), libraries with a strong visual impact, dependencies for a third-party script that you can’t defer…

These JS lines of code are called “critical JavaScript”. Group them into an identifiable file, commonly called critical.js. Like any JS file, the browser will have to fetch, parse and evaluate it before being able to execute it.

Even if you put all the optimizations in place to reduce the amount of data that needs to be transferred over the network (cleaning the unused code from the file, minify, compress, cache on the client and server side), the browser will still need to parse and evaluate the JavaScript. As that step takes a significant amount of time, you must really keep your critical JS file as streamlined as possible.

All other scripts should then be delayed, asynchronized, or moved to the footer, sometimes several of these things at the same time. Let’s take a look at these different techniques.

Move noncritical scripts at the bottom of the page

A very simple and intuitive way to defer the browser’s parsing of JavaScript files is to place the declarations at the end of the HTML page, just before the </body> tag. Doing so, the browser will not have any knowledge of the scripts until it has almost built the entire DOM.

Although this technique appears to be suitable for most of the cases, it presents a serious drawback. Not only it delays scripts evaluation, but it also delays their downloading which excludes its use for large scripts. Moreover, if your resources are not served by HTTP/2 or come from an external domain, you will also add a substantial resolution time to the retrieval time.

Obviously, since this technique occurs at the end of the DOM construction, we also remind you not to resort to scripts that use document.write, because the browser would have to completely rebuild it.

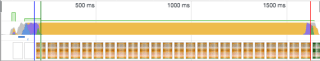

By pushing back the scripts at the end of the page, the completion of the display area is much faster but not definitive (a part of the content is altered by the execution of JavaScript)

How about injecting a dynamic <script> Tag?

As mentioned above, delaying the download of a script is not always the solution. You may prefer to make is asynchronous: the script is immediately retrieved without this phase blocking the construction of the DOM. Once available, the construction of the DOM is interrupted for the browser to parse and evaluated its content.

One way to do this is to not declare this script in the source of the page, but to use another script that injects it directly inside the DOM. This technique, called dynamic script tag, is the backbone of most third-party services.

One of the main advantages of this technique is that you can choose when the script is injected. If you want to inject it immediately, you can use an immediately-invoked function expression:

<script>

(function () {

var e = document.createElement('script');

e.src = 'https://mydomain.com/script.js';

e.async = true; // See the following explanation

document.head.insertBefore(e, document.head.childNodes[document.head.childNodes.length - 1].nextSibling);

}());

</script>

But you can also delay the injection so that it only occurs when a specific event is triggered. Here is how you inject a script when the DOM is ready:

<script>

// IE9+

function ready(fn) {

if (document.attachEvent ? document.readyState === "complete" : document.readyState !== "loading") {

fn();

} else {

document.addEventListener('DOMContentLoaded', fn);

}

}

ready(function () {

var e = document.createElement('script');

e.src = '[https://mydomain.com/script.js](https://mydomain.com/script.js)';

e.async = true; // See the following explanation

document.head.insertBefore(e, document.head.childNodes[document.head.childNodes.length - 1].nextSibling);

});

</script>

You may be surprised by the use of a convoluted insertBefore instead of a simpler appendChild. I invite you to read “Surefire DOM Element Insertion”, by Paul Irish.

As interesting as this technique seems, it also has its drawbacks. First, the scripts injected this way are no longer evaluated sequentially in the order of their injection. So you can’t use this technique to inject several scripts that require one another.

Secondly, dynamic script tags are not fully asynchronous. As explained in the introduction, the browser makes sure that the construction of the CSS Object Model is complete before executing the JS code of the injected script. The script is consequently not executed immediately. In order to explain to the browser that the script can be loaded without waiting for the CSSOM to be built, you must add the async attribute to the script.

But be careful: a script, even with an async attribute, is always considered as a page resource. The window.onload event will therefore be delayed by its execution. If other scripts depend on this event, you should expect a delay.

Well mastered, the dynamic tag injection is one of the most efficient techniques with a fast built DOM and an almost immediate display. Beware, however, that the scripts are not executed in order!

async, defer, or both

async and defer are two attributes standardized by HTML5. They allow you to modify the browser’s default behavior when loading a script.

If the async attribute is present, then the script is fetched as soon as possible, then executed. The declaration order of the async scripts is not preserved: the scripts will be executed as soon as they are available. But please note that even if the script retrieval will not halt the DOM construction, their execution will do.

Here, again, a very progressive loading. On the other hand, as for the dynamic script, we lose the execution order of the JS.

If the deferattribute is present, the script will be fetched as soon as possible, but the browser will wait for the DOM tree to be complete before executing it. Since most browsers now implement a preloader, the behavior of a script with the `defer’ attribute is very similar to the behavior of a script placed at the end of HTML content.

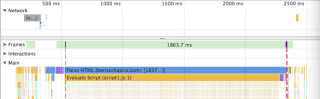

This alternative visualization mode helps fully understand the simultaneous evaluation of the DOM (in blue) and the script (yellow). Even if the script execution occurs later on, some time is saved.

As for using async and defer together, it’s not very useful, except for one use case, legacy support:

The defer attribute may be specified even if the async attribute is specified, to cause legacy Web browsers that only support defer (and not async) to fall back to the defer behavior instead of the blocking behavior that is the default. HTML 5.1 2nd Edition, W3C Recommendation 3 October 2017

Loading JavaScript files: get the control back, even on third-party scripts

We have seen that there is no shortage of techniques to asynchronize the recuperation and execution of scripts. Nevertheless, some scripts still need to be declared synchronous such as A/B test scripts, which sometimes intentionally block the render to hide the content from the user until the script has customized it (as these scripts often modify the visual aspect of the site, blocking the DOM and CSSOM makes sense).

Even in this situation, you don’t have to lose control. We encourage you to choose a solution that takes web performance into account. Some serious actors like Google Optimize, Kameleoon or Optimizely limit the time allocated to the recuperation and execution of their scripts. If this time is exceeded, the browser will abort the A/B script recuperation or execution. Do not hesitate to reduce this timeout period to a minimum to ensure the quality of your visitors’ experience.