Improving the speed at which a web page is displayed often means making the browser’s life as easy as possible. When the browser receives an HTTP response, it actually receives text encoded in bytes, where each byte or sequence of bytes represents a given character. If the browser does not have a clear information about the used encoding, it will waste time trying to guess and may fail in some cases.

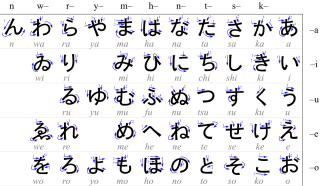

Although the Web is intended to be universal, the various human groups that use it have their own specificities. One of these specificities is language, especially when written. All textual content is composed of characters from a directory intended for a type of use. Hiraganas, for example, are phonetic system intended for the unambiguous transcription of the Japanese language.

Table showing the writing direction of hiraganas

by Karine WIDMER (CC-BY-SA-3.0 · Source)

To be able to designate each character unambiguously, we must assign a unique identifier to each of them. The whole set of identifiers will be called a character set. Once this correspondence table has been defined, each character need be converted into a sequence of bytes so that we can store or share them between computers. This is called character encoding.

Imagine that I use a character set to write text and a corresponding encoding to convert it to bytes, which I later send to you. How would you decode it, and read the content, without knowing which encoding, or set, I used? Eventually, you would have to use some of the most common character set & encodings you know, expecting the result to make sense… What could go wrong?

Replace a semicolon (;) with a greek question mark (;) in your friend’s JavaScript and watch them pull their hair out over the syntax error.

Ben Johnson (@benbjohnson), November 16, 2014

So yeah… not a great idea.

For example, the bit sequence 1100 0011 1010 1001 represents the character “é” in the UTF-8 encoding. If you decode this sequence assuming you have to use the Latin-1 encoding and not UTF-8, you will read “Ã ©”.

In Latin-1, the character “é” is represented by the sequence 1110 1001.

When the browser receives bytes from your server, it needs to identify the collection of letters and symbols that were used in writing the text that was converted into these bytes, and the encoding used for this conversion, in order to reverse it. If no information of this kind has been transmitted, the browser will try to find recognizable patterns within the bytes to determine the encoding itself, and eventually try some common charsets, which will take time, delaying further processing of the page.

To speed up the display of your pages, you must specify the content encoding into your HTTP response.

How to choose the right character set?

There was a time when hundreds of character encodings coexisted, all limited and not able to contain enough characters to cover all the languages of the world. Sometimes, no encoding was adequate for all letters in a single language.

Nowadays, Unicode – a universal character set, defining all the characters necessary to write the majority of languages – has become a standard, no matter what platform, device, application or language you’re targeting. UTF-8 is one of the Unicode encodings and the one that should be used for Web content, according to the W3C:

Everyone developing content, whether content authors or programmers, should use the UTF-8 character encoding, unless there are very special reasons for using something else. (If you decide to not use UTF-8, you must choose one of the few encodings that are interoperably implemented across all browsers.)

”Introducing Character Sets and Encodings”, W3C

Note: if you’re using a database to store your content on the server side, you may be tempted to also use the “utf-8” charset too. Beware: on MySQL and MariaDB, it’s an alias for “utf8mb3”, a UTF-8 encoding called “Basic Multilingual Plane” – or BMP – that only stores a maximum of three bytes per code point. Instead, you’d rather use “utf8mb4”, an encoding that stores a maximum of four bytes per code point. Otherwise, you won’t be able to use some popular characters, such as 🚀, otherwise known as “U+1F680 ROCKET”!

How to advertise your character encoding… and the best way to do it.

Before going any further, let’s take a look at the vocabulary in use.

Historically, the terms “character encoding”, “character map”, “character set” and “code page” were synonymous in computer science[…]. But now the terms have related but distinct meanings,[…] Regardless, the terms are still used interchangeably, with character set being nearly ubiquitous.

”Character encoding”, Wikipedia

We find this use of “character set” or “charset” to designate, in reality, an encoding, in the HTML specifications. We will do the same in the rest of this article.

One of the easiest ways to specify a charset in an HTML page is to put in a <meta> tag in the element:

<meta charset="utf-8">

Declaring a character set this way requires certain constraints to be respected, one of them being that the element containing the character encoding declaration must be serialized completely within the first 1024 bytes of the document, to ensure that the browser will receive the information with the first IP packets transiting through the network and can use it to decode the rest of the document. As the charset <meta> tag is the only one with this kind of requirement, the most common tip is to place it directly after the element opening tag:

<html …>

<head …>

<meta charset="utf-8">

If you’re afraid to forget this, don’t worry. This is obviously one of the checks that Dareboost will perform for you within our website quality analysis tool. However, you may find yourself in a situation where this declaration is not sufficient, and the browser does not take it into account. Why? Because the Content-Type metadata of the page may indicate another character set and in the event of a conflict, this information – defined in the page HTTP headers – has priority.

To make sure of the information transmitted through the page metadata, you can use our Timeline / Waterfall feature. Unfold the detailed values of your main document to view the response HTTP headers, including the Content-Type header, containing the encoding metadata.

To change this HTTP header, you may need the help of the person who managed the server, whereas it’s your hosting service provider or a person in charge in your organization, because the configuration of the HTTP headers is very specific to the web server in use, and you’ll need the appropriate administrative rights to be able to modify those server settings.

On Apache 2.2+, the configuration of UTF-8 as a default character set for your text/plain and text/html files involves the AddDefaultCharset directive:

AddDefaultCharset utf-8

For other types of files, you’ll need the AddCharset directive;

AddCharset utf-8 .js .css …

On nginx, you’ll need to make sure that the ngx_http_charset_module is loaded, then use the charset directive.

charset utf-8;

Here too, it is possible to refine the scope so that other types of files than text/html are delivered in utf-8, using the directive charset_types:

charset_types text/html text/css application/javascript

Of course, you can also configure the Content-Type HTTP header from your server-side scripting code. For example, in PHP, you can use the header() network function. Don’t forget to define the Media Type (or MIME type) of the body of the response, in addition to the character set.

header('Content-type: text/html; charset=utf-8');

Beware: if your pages are delivered by a Content Delivery Network (CDN), you may have to configure the Content-Type header in the CDN configuration, as most of them don’t pass on the headers they find on your servers.

Additional Resources

- The IANA Media Types list

- The Unicode website

- “Character encodings: Essential concepts”, on the W3C Internationalization website

- Still thinking that Character Encoding is a trivial issue? Look at “Anatomy of a Critical Security Bug”, by Andrew Nacin at Loop Conf 2015.